THE KOELSHIP: A FLAT COOLER FOR ALL OCCASIONS

Going on a tour of our small brewery at Saint Mars of the Desert is an easy task. If you can turn your head, you can see the whole place. But we almost always find ourselves lingering in one specific corner with our backs to the brewhouse. It’s because of a much misunderstood, little-known piece of 18-19th century equipment that always fascinates our visitors: our cooler (or “cooling tray”, or “coolship”, “Kühlschiff”or even “koelschip”). Let’s just refer to it as a “flat cooler” for now since that’s the proper English term for it.

Flat coolers are not entirely rare – once deemed obsolete, they have been making their way back into craft breweries since our friends in Maine, Allagash Brewing Company installed theirs a decade ago. A growing list of American and now British craft breweries have since installed these relics. But to properly understand the cooler, we need to go back in time to when they were a logical part of a typical brewhouse. Then we will follow them into traditional breweries who still use them, and perhaps even discover why they went away.

In the early days of industrial brewing, the post boil, pre-fermentation period must have been agonizingly long. Cooling down from the boil (100C) to fermentation temperatures in the teens likely required an overnight stand. Not ideal when you’re dealing with a fragile liquid such as unfermented wort. It’s the perfect place for all sorts of microscopic nasties to make their new home, fouling the flavor and longer-term stability of your beer.

The needed innovation for quick cooling was to increase the surface area of the wort, creating a greater cooling surface. If the cooling vessel was also made of a material known for its heat transfer properties, all the better. Therefore, eventually almost all coolers were built from copper, whose thermal conductivity is right at the top of the list. By the late 1890’s even wooden coolers were being lined with sheet copper. So the flat cooler, a vast shallow vessel outside the steamy brewhouse, was a technological advance that must have happened in every brewing culture at once. It’s just too obvious not to have done.

Wooden Kühlschiff at the Mönchshoff Brauerei Museum in Kulmbach. Credit Jim Barnes

In his 1957 book A Textbook of Brewing, Belgian brewing scientist Jean De Clerk refers to the vessel as a “flat cooler” and it is the first type of wort cooler he discusses in his book, albeit in a slightly derogatory way. He writes about how they were primarily constructed of copper, but also commonly made from iron plates riveted together with the tiny gaps jammed up with lead-coated paper. Contemporary brewers with flat coolers added strong air currents, employing something called the “Delbag” system of blowing to aid in precipitation of solids and “cold break” proteins. Later, he admits these Delbag systems are unique to “old out-of-date breweries with no adequate cooling plant.”

At SMOD we’re hardly “out-of-date” but we do produce a lot of steam when entering the cooler, often enough to reduce visibility to a “hand in front of your face” extent. It would be a frustrating and losing battle if we worried about each droplet being safe from harm. Instead, we choose to embrace the process and work with what we get from it. Our cooler is made from stainless steel: a great Sheffield invention, but 3,000 times less thermally conductive than copper. So we cool slightly slower than a traditional brewer might have. This is not a bad thing in our minds because one of the main reasons we built our flat cooler is for hop stands around 80C. Maybe you’ll agree that we get loads of fruit-like flavours from our hops doing it this way. After quite a short period, we run our wort from the cooler through our “adequate cooling plant”: a paraflow heat exchanger. This way we can go from the cooler straight into the fermentation vessel and pitch yeast – a quick temperature reduction of 60C.

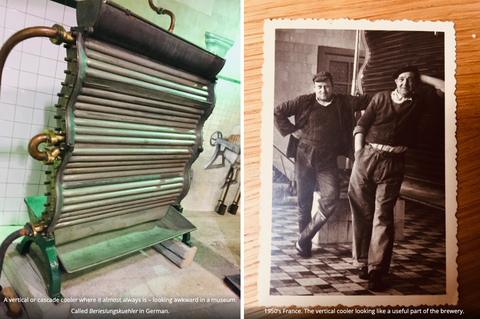

So, not all flat coolers are made of the same material, and as we’ll soon learn, they’re not all of the same dimensions. Furthermore, they’re not all used in exactly the same way. Our friend Ron Pattinson’s blog has a lot of flat cooler information and it’s interesting to see how and when they’re used in various breweries and how they evolve over time. In an article in the Journal of the Institute of Brewing of Bavaria in 1966, the classic arrangement is described as “coolingship, followed by an open upright cooler, and the use of a special fermenter for the first 24 hours”. The upright cooler, also referred to as a “cascade chiller” is now often referred to by the brand name of “Beaudelot” and seen mostly in brewing museums. De Dolle Brouwers in Esen, Belgium is the only brewery I’ve visited that still uses one – albeit updated with stainless steel coils. They’re hard to describe so I’ve posted a photo of one I saw at the Pilsner Urquell brewery in Plzeň. The wort ran to a trough on the top of the unit and then down the sides and over a series of horizontal, chilled pipes – literally clinging to the curvaceous sides. The Beaudelot thereby finished the job of cooling in the most delightful and risky fashion imaginable. From boiling and then a thirty minute stand in the cooler, then down to 14-16C with the Beaudelot for ales, half that for lagers. That’s how it was done.

Other types of refrigerators had been tried previously. In 1898 Frank Thatcher, a lab worker at Britannia Brewery in London wrote in the Country Brewers Gazette “the refrigerators where the wort flows inside and the water outside of the machine has become obsolete… the unpopularity of these refrigerators was determined by the inability of the operator to thoroughly clean the pipes.” So in the late 19th century the flat cooler was an upgrade over the counter-flow heat exchanger most of us use today.

Cooling at Pilsner Urquell in the early 20th century. Notice how shallow the coolers are.

The trad brewery: flat cooler upstairs empties by gravity to a vertical “Beaudelot” cooler a floor below. I took this photo at Pilsner Urquell.

The “special fermenter” referred to by the Journal is probably a tank or brink where the cold break is allowed separate prior to being transferred to a primary fermentation tank where the yeast is pitched. Other times it’s a vessel where yeast-pitched wort resides for a short time. This is sort of a German specialty that I’ve never heard used in the UK and I haven’t read much more about.

Most often flat coolers are entered after a drop through another vessel. Fitted with lauder-tun like false bottom plates, the main job of this basket-like vessel was to filter post-boil wort going to the cooler. Sometimes they’re in place of a hopback or more or less resemble one. Sometimes, as in Guinness’s West London brewery they are a sort of settling pool. This now demolished Royal Park brewery had a cooler that was roughly twenty-five feet square and six feet deep. That does seem incredibly deep but then I read the brewers didn’t want the wort falling under 80 degrees Celsius. So much for cooling! The highest post-flat cooler temperature I’d previously read was 75 (the lowest I’ve encountered is 20C by the way).

This strange depth confused me, but let’s read on.

E. J. Jefferey is quoted many times on Ron’s site from his textbook “Brewing Theory and Practice”. Published one year earlier than De Clerk’s book, Jefferey has a nearly identical snooty attitude towards the flat cooler, but he solved my mystery by pointing out that flat coolers evolved into a much deeper vessel that became known as a “receiver”. This wort receiver was post-boil, and usually post-hopback (where the protein was filtered out of the wort through a bed of whole cone hops). Wort would never sit still in this receiver long as it was constantly moving through an outlet to a refrigeration unit as it filled. So here we have the best technology in 1956: a deep version of the old flat cooler that doesn’t cool but rather drains into an “adequate cooling plant”. The end of the flat cooler in pre-craft, industrial brewing was now within sight. But what was the role of this deeper “receiver”?

The flat cooler at De Dolle Brouwers taken on my first visit in 1996. Note the basket.

At first it occurred to me that these modern receivers may have reduced infection by reducing the length of time wort stands in open air. The hot break would be taken out by the hop back, but the cold break would now be allowed to stay in solution. This is a step backwards and forwards at once. Meanwhile those much-maligned “Delbag” brewers (you remember them from the De Clerk book) in their shoddy old breweries were actually delivering more wholesome wort to their fermentation tanks without that cold break in it. I was firmly on the Delbag side of things or at least I thought so until I read about “trub sacks”. Trub sacks were conical flannel bags, which were packed with the moist hot and cold break (“cooler sludge” left behind in the flat cooler), then hung over open fermenters to drain. Yuck! I’m flipping sides again. I’ve seen photos of trubsäcke still in use as recently as the mid 1990’s in Franconia (in the book Bierstadt Bamberg, page 49, Brauerei Greifenklau, Bamberg).

The financially carefree Delbag brewers were building “recovery plants” that drained trub right from the flat cooler, filtered and pasteurized the wort and then pumped it over to fermentation.

On an aside… Years ago I was hanging out with the head brewer of a famous Belgian abbey beer brewery and found myself describing to him my perfect brewery. He responded, “Ahhh, you like dirty old breweries.” I wish I had this knowledge back then. I would have said, “Yeah, I’m a total *Delbag!”

Another aside, these days Belgian brewers are over-associated with with the flat cooler. Probably because Lambic breweries still have a vital use for them. That and a few now out-of-date photos from Michael Jackson books. With the help of Brother Thomas of Westmalle, the Saint-Sixtus Abbey brewery at Westvleteren did away with their coolship in 1976 and with it what they refer to as their “sweet-and-sour beer recipe.” Four years later nearby De Dolle brews their first batches of Oerbier – a sweet-and-sour beer made using a flat cooler. The new radicals and the ancient monastic tradition crossing each other like ships in the sea. Fascinating stuff I think.

Another photo by Jim Barnes in Kulmbach. This small flat cooler pretty much sums it up.

Today at SMOD and to a small number of brewers around the world who use the flat cooler in the more traditional sense, cooling in itself isn’t the main reason. Our friend Andreas Gänstaller of Gänstaller Bräu in Schnaid, Franconia, Germany uses his kühlschiff every brewday and his vintage facility was one of the inspirations for our small brewery here in Sheffield. “I’m a big fan of kühlschiff because all of the trub and cloudy stuff from the wort really saddles down on the bottom – clears out very well. All the negative stuff in the wort goes away, like D.M.S.” You read this a lot from German brewers, they like their wort really clean and the flat cooler does the job.

At the Mönchshof Brewery Museum. Notice the motorised “wind wing” in the centre of the cooler. Later designs have the wing installed underneath the cooler, so as not to disrupt the foam and steam cap on the wort. Is this similar to the Delbag system? I’d love to know. Also, notice that trub leaves the Kühlschiff, is boiled, pressed and sent to the vertical cooler. Photo Jim Barnes

Andreas says he does his stands in his kühlschiff until about 75C and then moves the wort to the paraflow refrigerator. I’d say we’re about the same here at SMOD. There isn’t much reliable modern information about these flat cooler stands in terms of length and temperature. Kris Herteleer at De Dolle casually told me on my most recent visit to his brewery that he does an hour stand and gets the wort down to 90C. At least one of those numbers doesn’t seem real to me. But I love Belgian brewers for their cheeky misinformation – it’s a refreshing change to our oh-so-earnest, hand on your heart, craft beer bubble.

For what its worth Louis Pasteur mentions wort cooling on page two of his Studies on Fermentation saying “as long as wort is at a high temperature it will remain sound; when under 70 C, and particularly when at a temperature of from 25 C to 35 C, it will be quickly invaded by lactic and butyric ferments. Rapidity in cooling is so essential that to secure it recourse is had to special apparatus.” This was originally published in 1879 so he’s talking about the same stuff we’re reading about in this piece!

Both De Dolle and Gänstaller Bräu are interesting also because they’re basically small 19th century country breweries built in a much more simple way than the city plants De Clerk and Jeffereys were using as their models in the mid-1950’s. If I’m not mistaken both breweries are shipping wort directly from the kettle and directly through refrigeration into fermentation, with no other process tanks in that span. Both breweries also hop their flat coolers. De Dolle’s wort passes through a perforated steel basket filled with whole cones that sits at the head of the koelschip. Andreas spreads T-90 hop pellets in an area of his 268 square foot kühlschiff he knows to be cooler than the others. Though I’ve never seen it written (perhaps it’s nothing more than a folksy anecdote) but there is a theory that hop oils rise to the surface and become a barrier to the air. If you tilt your head and catch the light in the right way you can see oily areas floating on the surface of our flat cooler, but it’s hardly a continuous film.

The only writing I’ve seen discussing the top surface of the wort on flat coolers has to do with fob and it’s pretty interesting. Flat coolers in some breweries could lose as much as ten percent volume of wort due to evaporation. Ten percent is way too high to ignore and would leave the brewer no choice but to adjust colour, bitterness, gravity and pH in the brewhouse to accommodate for these later process losses. An easier remedy was getting the wort to fob on the way in to the cooler, so the foamy cap would stop this phenomenon. I can hear the voices already – how do you get this wort to fob without introducing oxygen? All I can tell you is that from everything I’ve read, brewers were aiming to get oxygen into the wort in the flat cooler. It was believed to be good for the beer.

I have a memory of Dr. Michael Lewis, Professor Emeritus at U.C. Davis strongly rebuking our classroom for the mere mention of “hot side aeration” framed as a worrisome problem. At SMOD we don’t worry about it either. If we don’t get enough of it from our flat cooler stand, we definitely make up for that by pumping it straight into the hot wort pre-heat exchanger.

Finally, having a PhD microbiologist on our staff is a great asset and if you ask Martha, she’ll tell you our wort isn’t free of micro-organisms. She has seen lacto on her microscope and we have detected Ethyl Butyrate in sensory evaluation that may or may not have come from the coolship. Lactobacillus isn’t the worst thing in the world and most likely plagues non-coolship brewers as well. But as a token weapon against the potential souring of our beer we employ hop bitterness and when used we have not seen much lacto growth and certainly no souring. So “New England IPAs” went out the door in favour of “Koelship IPA” which allows us to make the beer we need to make. We definitely believe that our beers are DMS-free because of the coolship, we have gorgeous head stability and the hop-stands are epic.

I think I’m running out of things to say about the humble flat cooler and its use in making clean beer. I’ll give my old friend Jeff Beigert the last word on the subject, he’s a long time former Boston brewer like me, but much more accomplished. He’s also former Head Brewer at Avery Brewing in Colorado. Presently he’s the New Belgium Brewing Sponsored Fermentation Science & Technology Instructor & Brewmaster in the Food Science and Human Nutrition at Colorado State University.

Me: “Hey Jeff, can you think of any good reasons to use a coolship in a craft brewery making “clean” beer?”

Jeff: “Not really.”

So there, I saved the headline for last. But if you’re like me you just don’t care. Long live the flat cooler.

The SMOD Koelship: Image Credit: Matthew Curtis

*******************************************************

The other use of the flat cooler.

It will have occurred to the more adventurous beer drinkers among you that this article has missed some of the point entirely. Most flat coolers being built right now are in fact referred to as coolships, and are installed ostensibly for the production of naturally soured or “spontaneously fermented” beers. This is a fascinating use of the cooler that takes advantage of the riskier aspects of this vessel. The evolution of spontaneously fermented beer as a genre of brewing is outside the remit of this article, and for another time. However, it seems remiss not to mention this far trendier use of the cooler. In this situation, wort is left in the coolship overnight with the hope that as many microbes will float into the liquid as possible, thereby triggering a “spontaneous” fermentation from natural flora, allowing the brewer to strutt their stuff at the next festival and use words like “terroir”. If the traditional use of a flat cooler was overshadowed by fear of infection, the lambic brewers must conversely fear that not enough infection will occur.

My suspicion has always been that a lot of the magic of these beers, rather than sprouting “spontaneously” from a single night in a cooler, is from the repetitive use of the cooler combined with wooden fermentation and maturation vessels, which creates a growing microbial foundation inside the wood and in the surrounding fermentation areas.

In Raf Meert’s 2022 book Lambic: The Untamed Brussels Beer. Origin, Evolution and Future, he gets to precisely this point on page 250. Lambic brewers had the same suspicion as me: the wood was more important for inoculation. On the very next page however he cites two experiments that point to the cool ship as playing the most important role in creating the microbial mix that lambic is known for. It’s worth noting that the depth of the wort in these vessels is insanely shallow compared to SMOD but no more shallow than what we see in Pilsen. Over cooling the wort to a lacto-friendly temperature range (50c or less) is probably a critical difference between “clean” and inoculated cool ship worts. Lactobacillus can multiply its population insanely rapidly.

The Meert book is a brilliantly sober and factual look at lambic. I would highly suggest purchasing it. Among the many revelations from this book is a description from 1829 describing “spontaneous fermentation” as done in the United Kingdom (page 214).

If you walk around a lambic brewery the atmosphere is thick with the perfume of the beer produced there – much more so than in any other type of brewery I’ve visited. To me it’s better than anything to be in one of these breweries, knowing you’re inside this ripe environment, the very environment that gives the beer its evolving and insanely complex flavour. Beer-people enjoy talking about “sense of place” these days in reference to spontaneous beers, which might send your imagination to the banks of the Seine or flowery meadows or any number of bucolic jigsaw puzzle type scenes. What I know, and love is that the “place” in beer, no matter what type of beer it is – is the brewery. Breweries are my favourite places bar none except for maybe the pub.

*No offence is meant to the modern Delbag air filtration company. I’m sure they’re great.